By Sister Chan Lac Hanh

What is the right thing to do?

In Plum Village, France, we have just finished the 2023 – 2024 Rains Retreat in which ethics was the central theme. And more specifically the Buddhist approach to a global ethics. As monastics in this tradition, we commit to living our lives according to a certain ethical code, coherent to the novice or Bhikshu or Bhikshuni precepts. For me, living in such a way not only protects my mind-body-spirit and its three karmas of thought, speech, and action in the present, but also transforms the residue of my past, assuring a brighter, clearer future, less tainted by regrets and remorse. It is about living my life in a way that is deeply rooted in well-being, wholesomeness, understanding, compassion, love, and peace, and continuously orientates me in that direction.

What is the right thing to do?

I feel like this is a question that I have faced many times in my life. Suddenly I would find myself inert on a seeming crossroads, paralyzed with the realization that whatever decision I make would take me into very different directions and shape the course of my life’s journey. My heart and mind would be in conflict as I agonized over what to do, as I imagined the possible outcomes and weighed the pros and cons. I always grappled in making big decisions, as I always felt that there must be “a right thing to do,” although it was not always apparent and somewhat elusive to me.

What is the right thing to do?

On 29 December 2014, I met my birth mother. Or re- met her. After being with her for the first year of my life, I spent the next 40 years apart from her. Our lives had unfolded in drastically different and unexpected directions and yet we met again in the city where she had given birth to me. When we met in the assisted-living hospital where she lived, she was paralyzed and unable to speak after having had a cerebral stroke about 15 years prior. Everything that I had been piecing together over the past years crumbled in that meeting. All hopes of discovering more details about my origins narrative, which had fueled my birth family search, and that I had learned to some degree through the reunion with my birth father two years before, dissolved in an instant.

Trying to understand the past no longer became so important. “What do I do now?’ and ‘how do I move forward?” became more relevant. And I had no idea. What kept rising in me was laden with “shoulds” or what I perceived was expected of me. All were figments of my imagination, as no one was voicing to me what they felt I had to do. My birth mother was alone and couldn’t speak, so she was not telling me what to do. Her blind elder brother (her guardian, whose permission I had to obtain in order to meet her) and his family also never asked for anything from me. Because I was adopted and was not raised by her, my family and friends couldn’t fully understand why I felt responsible in some way to take care of her.

But I did feel responsible in some way. And also completely helpless in what was the right thing to do given the complexities of that situation. I was her daughter by blood, but I now had another mother. I was not able to speak her language in order to communicate with her, nor did I understand the intricacies of Korean culture and families. Most importantly, I didn’t know anyone who had even remotely been in a similar situation to guide me through this unknown territory and journey that I was facing.

What is the right thing to do?

The suffering that arose from those experiences completely overwhelmed me into a state of inertia and despair. It is what brought me to Plum Village for the first time. I had been reading Thay’s books since 1999. His teachings and practices accompanied me on my Ashtanga Yoga path that I was committed to practicing and teaching over the same amount of years. I deeply resonated with Thay’s teachings that were born out of a war-torn country – divided by ideologies – and his life in exile as he refrained from taking sides, always calling for peace. Peace for his country, peace for the world, peace within oneself.

I had always wanted to go to Plum Village, but the conditions were never sufficient. Even though I already had a spiritual practice, it was not wholly nourishing nor transforming my intense suffering after reuniting with my omma (birth mother). I reached out to close friends in my international Ashtanga Yoga community, curious about what had helped them in deep crises when they felt our practices were not enough. I received a deluge of responses, spanning all realms of healing the body- mind-spirit from diverse traditions and cultures.

One friend, who had delved deeply into Vipassana meditation practices with me over the years, sent me a link with no written message. When I opened it, it was for an article reporting that Thich Nhat Hanh had just left the hospital in Bordeaux to return to Plum Village after having recuperated sufficiently from his stroke. I instantly knew that I too needed to go there.

What is the right thing to do?

I arrived in New Hamlet at the beginning of the Spring Retreat in 2015. Already during the first week, I was beginning to experience a slight shift in my despair and gradual transformation of my suffering through the daily practices and teachings, as well as with the support of the Sangha. I ended up staying the whole Spring Retreat during which I received the Five Mindfulness Trainings, which I felt were a beautiful expression of how to live an ethical, compassionate, heart-centered life of understanding and peace.

I also recognized and felt my latent monastic seed being watered. However, I was still embedded in the material world. I had a beloved partner, who had accompanied me through everything during the past eight years, and I was still not fully resolved about what to do about my omma. Over the next few years, I continuously sought ways to return to Korea to be geographically closer to her and to learn more about myself and ancestral culture; and also returned to Plum Village to deepen my practices and to reconnect with the Sangha.

Through Ashtanga Yoga, I was invited multiple times to teach in Korea. It was such a powerful, healing experience to share the yoga practices there. Simultaneously through Thay’s teachings of how to practice with grief, how to heal the wounded inner child, how to practice transforming the transmissions of ancestral, generational, cultural and collective suffering, etc, I was slowly able to heal some of my internal spaces.

However, I always felt a bit blocked and slightly resistant whenever Thay’s teachings spoke about a mother’s unconditional love and care for her baby, or how to practice with our mother as a 5-year-old child, or how to walk with our mother. I could not fully connect with my omma through those practices, because in my mind, it did not reflect my experiences with her.

For me, the beauty of the mindfulness practices and teachings, done continuously over time, is that I start to drop out of the mind and into the heart to a deeper level of understanding and healing. On one trip to Korea, the hospital told me that my omma was now bed-ridden and unable to eat solid foods since January 2017, and was being fed by a tube through her nose. By this time, it had been about 20 years since her stroke, and I was amazed at her resilience of spirit and often contemplated what it meant to be alive and what it was that kept her living.

In 2018, I made the radical decision to move to Seoul, after receiving an invitation to teach Ashtanga Yoga there indefinitely, even though my partner, Bruno, decided not to accompany me. Although it was a heartbreaking decision, I inherently felt that a deeper healing was necessary and had to be faced by myself. Who I was and how I was perceived in Korea alone was radically different than when Bruno was by my side. And strangely enough, somehow our separating was also a way of saving our relationship and keeping our love intact, as my constant coming and going was starting to take a toll on our togetherness.

What is the right thing to do?

Living and teaching in Korea was one of the most diffcult things I have ever done because of the myriad of subconscious and unconscious, latent seeds that were touched and triggered in my store consciousness. It was also one of the most beautiful and enriching experiences, as I was able to connect with the immense generosity, kindness, warmth, and love of the people and culture, healing the abandonment and separation that lay deep in my heart.

The unforeseen COVID pandemic radically interrupted life as we had known it. The local and global restrictions brought into question again the trajectory of my life. Due to the social-distancing regulations, I was unable to visit my omma in the hospital and I began to reassess my situation and my life path. During this time that the world came to an unexpected, collective pause and we all relied on a more online rather than in-person presence, Plum Village resurfaced in my consciousness and I reconnected with my deepest aspirations.

As the pandemic drew on and life became more uncertain, I dove deep within once more for guidance and clarity. Even though I had originally thought that I would stay in Korea at least until my omma passed, I decided to move back to Europe and join the 2021 Rains Retreat in New Hamlet to see if my monastic aspiration was still extant. Before leaving Korea, as the world was beginning to open up again and restrictions were slowly lifting, I was allowed a 20-minute farewell with my omma, in which I expressed my love and gratitude.

I was told that even though she had been able to eat semi-solid food again, she had not opened her eyes for the past nine months. I immediately wondered what it was that she didn’t want to see. As I held her hand, gently speaking to her in my newfound, limited Korean, I thanked her for giving me life and for coming back into my life, and wished her peace in letting go. I knew that it would most likely be the last time I saw her in that form. I left Korea, my heart heavy, yet full and open, and relatively at peace.

And that is the right thing…

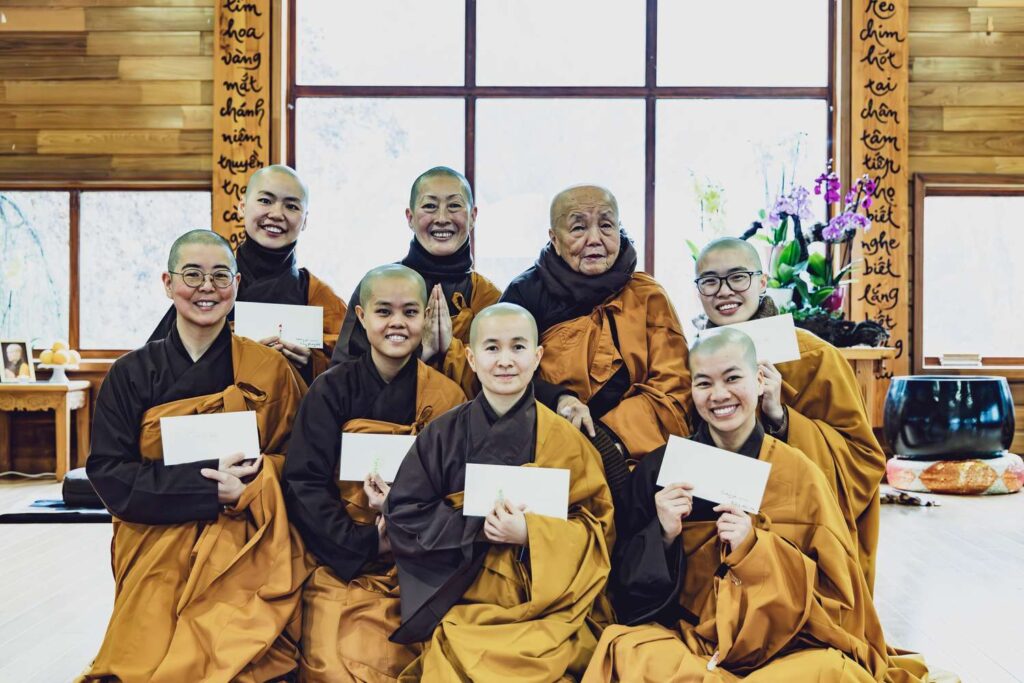

My omma passed away on 30 July 2022, while I was an aspirant in New Hamlet, a few months before I was ordained as a novice nun in Thai Plum Village. Sister Chan Khong was present at my ordination and cut the first lock of my hair before my head was shaved. Sister Chan Khong had been a pivotal force in why I had chosen New Hamlet when I first came to Plum Village in 2015. After reading her inspiring book, Learning True Love, her author’s biography stated that she resided and practiced in New Hamlet. That was the only guidepost I needed.

She is a warm, compassionate and inspiring presence; and to this day, she is still an indomitable force. After having sustained a fall and hip surgery, she’s often in a wheelchair. Through various forms of physical therapy, she could be seen practicing assisted-walking around the hamlet. One day, after formal lunch, I was moved to tears when she was able to walk the whole length of the meditation hall in Lower Hamlet with only the support of her walking sticks.

I later expressed to her that something inside me was profoundly touched as I recognized that during the reunion journey with my omma, there was a deep, unspoken and impossible hope that she would one day get up from her wheelchair and walk into my arms to embrace me. Sister Chan Khong opened her arms and folded me into a comforting hug. Her determination and perseverance in recuperating her mobility were inspiring. Witnessing this process, something deeper inside me was also healing. One day after formal lunch, when she was able to walk unassisted the full length of the Upper Hamlet meditation hall, I was again moved to tears.

Since my omma has passed, I have been better able to touch her inside of me and to feel that she is inherently a part of me. She is no longer confined to a wheelchair or bed or hospital room. All the grief and helplessness that I felt throughout that journey has started to ebb and transform through the varied Dharma doors and practices, especially during walking meditation with the sangha.

I feel that sometimes we don’t necessarily experience transformation and reconciliation with the intended person, but somehow we are able to heal internally through the various situations that arise, and the people we come into contact with. And often when we least expect it. The words Thay has shared in the guided meditations and practices and that he has written in his calligraphy no longer lie flat on the page. “I walk for you” are no longer just four meaningless words to me. They are alive at the core of my being when I am present and remember to practice. With every step, through every breath.

Sitting here and looking back, I’m not sure if there is ever a “right thing” to do. Life and its unfolding are so subjective due to different causes and conditions. However, when we can abide by certain ethical and moral codes that are rooted in understanding, compassion, and love, and move us toward wholeness, rather than fragmentation or division, I feel that in any given situation, there is really only one thing we can do. And that is the right thing.